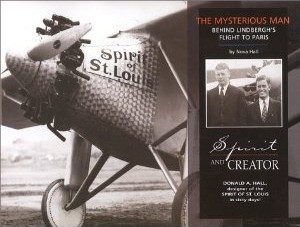

The Spirit of St. Louis after being designed and built in 60 days. Photo by Donald A. Hall Sr.

The Spirit of St. Louis Story

Written by Nova Hall in association with the Charles and Anne Morrow Lindbergh Foundation

Young airmail pilot

It was in the fall of 1926, during the lonely hours flying the mail at night, that a young airmail pilot for Robertson Aircraft Corporation, had his first thoughts about flying across the cold Atlantic waters in an attempt to capture the elusive Orteig Prize. His name was Charles A. Lindbergh.

The $25,000 Orteig Prize, which had been offered since 1919 by a prominent New York hotel businessman, Raymond Orteig, for the first non-stop flight from New York to Paris, was not what interested Lindbergh. Instead, he was intrigued by the idea of demonstrating publicly that airplanes could safely link the United States and Europe, and at the same time, giving greater credibility to civilian pilots and commercial aviation. As for the danger of such an incredible flight, Lindbergh believed that neither the weather nor the dangers of a transatlantic crossing could be any worse than what he had already experienced pioneering the air-mail routes from St. Louis. Rain, snow, ice, and fog, could be compensated for with experience and through logical thinking.

The $25,000 Orteig Prize, which had been offered since 1919 by a prominent New York hotel businessman, Raymond Orteig, for the first non-stop flight from New York to Paris, was not what interested Lindbergh. Instead, he was intrigued by the idea of demonstrating publicly that airplanes could safely link the United States and Europe, and at the same time, giving greater credibility to civilian pilots and commercial aviation. As for the danger of such an incredible flight, Lindbergh believed that neither the weather nor the dangers of a transatlantic crossing could be any worse than what he had already experienced pioneering the air-mail routes from St. Louis. Rain, snow, ice, and fog, could be compensated for with experience and through logical thinking.

Funding historic transatlantic journey

As he considered how to go about getting funding for what would become an historic transatlantic journey, he devised using his personal savings, but realized that would not be enough. He organized a presentation for a number of local St. Louis businessmen, hoping they could see his vision for commercial aviation, the proven possibilities of current modern aircraft, and agree to sponsor his attempt to make a trans-Atlantic crossing. “First, I’ll show them how a non-stop flight between America and Europe will demonstrate the possibilities of aircraft, and help place St. Louis in the foreground of aviation. Second, I’ll show them that a modern airplane is capable of making the flight to Paris, and that a successful flight will cover its own costs because of the Orteig Prize,” Lindbergh later wrote in his book The Spirit of St. Louis.

Major Albert Bond Lambert was the first to pledge $1,000 toward the flight, after Lindbergh committed his own personal savings of $2,000. By February 1927, Lindbergh received complete financing for his flight from Harold M. Bixby, Harry F. Knight, Harry H. Knight, Albert Bond Lambert, J.D. Wooster Lambert, E. Lansing Ray, Frank H. Robertson, William B. Robertson, and Earl C. Thompson. The group became known as the St. Louis backers.

Single-engine monoplane with a single pilot

Because of the support from the St. Louis backers, Lindbergh was given the freedom to pursue his dream of crossing the Atlantic in a single-engine monoplane with a single pilot, which he knew was safer and more likely of success. Mr. Bixby would later name the plane, the the Spirit of St. Louis. Having been turned down by all the major aircraft manufactures, including his attempt to purchase a Bellanca (the only pre-built plane available for such a flight), Lindbergh traveled by train to San Diego and Ryan Airlines, Inc. at the insistence of his St. Louis backers. He had queried the small company before being turned down by Bellanca.

Donald A. Hall Sr. at work

Ryan Airlines of San Diego

If Ryan Airlines of San Diego could complete a specially modified aircraft, it would need to be ready in two months. Though a possible task, as far as Lindbergh was concerned his chances for success were waning.

Arriving on February 23, Lindbergh soon realized that the decision whether to place an order with Ryan, and their ability to build such a plane in 60-days, rested in his estimation on one man, Donald Hall, the new Chief Engineer. The two men, scholars of current aviation technology in there own right, and experts in their fields, had much in common. Both had attended flight school in Austin, Texas at Brooks field a year apart. Hall was 28 and Lindbergh 25. Fueled by a common interest, there was a spark between the two men, and on February 25, Lindbergh placed his order for the Spirit of St. Louis.

Hall and Lindbergh

Immediately, Hall and Lindbergh started the work that would develop into a solid plan for crossing the Atlantic. Most issues the two agreed upon, while on other points they compromised. Lindbergh and Hall both believed that the decision to use a single-engine plane was best since it offered less chances of failure if a proven engine was chosen, like the Wright Whirlwind J-5C. The two men also agreed that the main fuel tanks should be in front of the pilot, yet Hall was concerned with forward visibility. Collaborating on a constant basis meant the two men rarely parted each other’s side. Each knew the tragic result if a single fuel line busted, if icing weighed down the plane, if a major navigational error occurred, or if pilot fatigue overwhelmed Lindbergh.

It quickly became clear to Hall that a completely new design was a better option compared to modifying the older Ryan M-2 model. “…It was concluded that a redesign of the production model 3-seater, open cockpit, Ryan M-2 could not make the 3600 mile flight between New York and Paris with ample reserve fuel, and that a new design development was necessary,” Hall later wrote in the appendix of The Spirit of St. Louis.

February 28, 1927, The Spirit of St. Louis begins

Lindbergh’s planning

While the NYP (New York-Paris) design was eventually “frozen”, it remained fluid throughout the 60-days as new concepts were incorporated like the periscope. Lindbergh too had much to plan, decide, check, and re-

Lindbergh,Mahoney, Hall – DAH Collection

check. In those 60-days of thinking, worker inspections, and test-flights in the Ryan M-2, Lindbergh taught himself the fine art of aeronautical ocean navigation, which was new and unproven. Based off sailing charts and gnomonic maps, Lindbergh became skilled at navigation according to nautical shipping lanes and navigation by the stars. Hall proved to be helpful in this task as well, providing drafting equipment and checking Lindbergh’s calculations as needed.

Lindbergh carefully planned every detail of his trip and evaluated the necessity of every item he would carry. Opting to leave his parachute behind so he could carry more fuel, he also passed on a radio. He even went so far as to trim the edges off his maps, remove unnecessary pages from his notebook, and declined to take night-flying equipment in order to conserve weight on the plane.

Ryan Airlines, 60-day task

The employees at Ryan Airlines too, leant themselves to the daunting 60-day task before them. While the initial secretiveness that surrounded the plane’s construction eventually became common knowledge in the factory, each worker devoted himself or herself to the success of Lindbergh’s flight. Men and women worked late into the night, while a young Lindbergh quietly walked about the factory, silently watching as they completed their work.

Hall and Lindbergh would ultimately spend the majority of time and effort in designing and planning the young aviator’s successful flight across the Atlantic. Between them and the Ryan Airlines, Inc. team, they had accounted for every possibility whether remote or uncommon. The chief concern, however, was pilot fatigue from the start. Yet, this too had been accounted for in the planes touchy controls and only “satisfactory” stability. Nothing would be assumed or left to chance.

Orteig Prize long shot

When Lindbergh registered with the National Aeronautic Association as a contestant for the Orteig Prize, he was regarded as the long shot. All the contestants that had previously registered had multi-engine planes with multiple pilots. Only Lindbergh planned to fly alone in a single-engine plane. Later the single-engine Bellanca was registered, but it too would have multiple pilots. In spite of his flight experience and military training, some even called the young aviator a “flying fool”.

For pilots attempting the Prize, the rudimentary instrumentation, inaccurate weather reporting, and inadequate lighting were obstacles to be confronted with skill and determination. However, building an airplane capable of getting off the ground with the heavy load of gasoline needed for a 3,600-mile flight was the greatest challenge of all. When Lindbergh thundered down the runway in New York, the Spirit of St. Louis weighed in at 5,250 pounds, of which 2,750 pounds was gasoline (or 450 gallons), which was a feat all unto itself. Only one other plane attempting the Orteig Prize had taken to the air with that much fuel, and it was never seen again.

(Spirit of St. Louis

The first flight of the Spirit of St. Louis

View additional pictures from the Donald Hall estate Photograph Collection. All photographs are protected by federal copyright law.)

April 28, 1927, first flight

On April 28, 1927, Lindbergh wired Harry Knight in St. Louis to inform him that the plane was ready for its first flight. That first day, as captured by the photographs and memories of Donald Hall, was extraordinary. With all their hard work and diligence, Ryan Airlines had met their 60-day goal and as the Spirit of St. Louis lifted off a cheer erupted from the assembled factory crew. Their dreams and hopes were embodied in that silver plane and young aviator Charles Lindbergh.

On April 28, 1927, Lindbergh wired Harry Knight in St. Louis to inform him that the plane was ready for its first flight. That first day, as captured by the photographs and memories of Donald Hall, was extraordinary. With all their hard work and diligence, Ryan Airlines had met their 60-day goal and as the Spirit of St. Louis lifted off a cheer erupted from the assembled factory crew. Their dreams and hopes were embodied in that silver plane and young aviator Charles Lindbergh.

The next few days were filled with flight performance testing, minor adjustments to the plane, and the fuel load testing conducted away from the Press at a secret location. Camp Kearny, an abandoned WWI parade ground near present day Miramar, proved perfect. These tests illustrated to Lindbergh and Hall, after he had graphed the performance curves, that the plane had an abundance of power even when the fuel load was increased to 300 gallons. Lindbergh would later push those performance curves at Roosevelt Field in New York.

To Lambert Field in St. Louis

With flight-testing completed, Lindbergh waited for a break in the weather, and finally on May 10 he took flight in his gleaming silver Spirit of St. Louis. Two Army observation planes and a lone Ryan M-2 carrying Hall,

Mahoney, Edwards, and its pilot escorted the plane till they too turned back. Flying east alone into the coming night, Lindbergh arrived at Lambert Field in St. Louis the following morning, May 11, 1927, establishing a non-stop speed record of 1,500 miles in 14 hours and 25 minutes.

Mahoney, Edwards, and its pilot escorted the plane till they too turned back. Flying east alone into the coming night, Lindbergh arrived at Lambert Field in St. Louis the following morning, May 11, 1927, establishing a non-stop speed record of 1,500 miles in 14 hours and 25 minutes.

Telegraphing these results back to Ryan Airlines and Hall, it proved their measurements had held, and the plane was performing well. Spending the night in his former boarding house, the next morning Lindbergh left for New York, hoping he could beat the other competitors.

Charles Lindbergh & The Spirit of St. Louis

Charles Lindbergh and the Spirit of St. Louis

View additional pictures from the Donald Hall Photograph Collection. All photographs are protected by federal copyright law.

Lindbergh arrived in Long Island on May 12, 1927

The mood was tense as Lindbergh and the two other contestants waited day after day for the weather to clear enough to allow a successful take-off. Spending hours reviewing weather charts, watching the mechanics tend his plane, dealing with the incessant media, while diligently guarding his take-off plans, Lindbergh found time to take in some of the sights of New York City.

Charles Nungesser and Francois Coli Missing

In the weeks preceding Lindbergh’s take-off, the magnitude of danger for the flight became even more eminent in the public’s eye. Just two days prior to Lindbergh leaving San Diego, the famed French pilots Charles Nungesser and navigator Francois Coli had left Paris for New York in a single-engine biplane on May 8, and had disappeared over the Atlantic Ocean. The odds, it would seem, were against any attempt to cross the Atlantic.

Newspapers were peppered with stories of plane crashes and fatalities surrounding the competition. French pilot Rene Fonck crashed on takeoff from Roosevelt Field, Long Island on September 21, 1926, killing two crewmen. A third plane, the American Legion, piloted by Noel Davis had also crashed earlier that month on April 26. Both Davis and Stanton Wooster his co-pilot had been killed. Both Richard E. Byrd (who would later fly over the North Pole) and Clarence D. Chamberlin, a noted aviator piloting the Bellanca, each had minor accidents during the testing of their planes in April of 1927. Now Byrd and Chamberlin waited with Lindbergh for a final attempt.

Decision to forego a radio

When pressed in New York about his decision to forego a radio, Lindbergh said, “When the weather is bad you can’t make contact with the ground. When the weather isn’t bad a pilot doesn’t need a radio.” Lindbergh had already lost his patience with the incessant and sensationalistic press. To make matters worse, he had not yet become technically eligible for the Orteig Prize, which stipulated that 60 days must elapse between acceptance of his entry papers and take-off of the flight to qualify. His St. Louis backers told him to fly when he was ready, despite the Prize.

Weather forecasts offered little hope

May 19 was a dreary day. The weather forecasts offered little hope of a clearing in the weather in the next few days. That evening, after touring the Wright plant in New Jersey with some of his new friends, and B.F. Mahoney the owner of Ryan Airlines, Lindbergh and some others had planned to attend the Broadway show “Rio Rita.” Before they arrived at the theater, however, they stopped for one more phone call to the weather bureau. There was good news, yet no one had informed him earlier. A break in the weather was predicted, with high pressure beginning to clear patches of clouds over the Atlantic. Suddenly an early morning departure was possible. The group headed back to the airfield to begin making preparations and final inspections.

After working on the plane for a few hours, Lindbergh returned to the hotel just before midnight. If he was to be ready at daybreak, as he had planned, he needed to get some sleep. Upon arriving at the hotel, however, Lindbergh was confronted by a throng of reporters anxious to interview him. Word of activity in his hangar had already spread. Lindbergh excused himself as quickly as possible. Once in bed, his mind raced with a thousand thoughts, questioning, reasoning, calculating, and reviewing every decision he had made to this moment. At 1:40 a.m., he realized there was little hope for sleep.

Misty Friday morning, May 20, 1927

At 2:30 a.m. on a misty Friday morning, May 20, 1927, Lindbergh rode from the Garden City Hotel, where he and the other contestants were staying, to Curtiss Field to prepare for take-off. Even at that early hour, 500 on-lookers waited. At 4:15 a.m. the rain stopped. Lindbergh ate one of the six sandwiches he had been given the night before and ordered the Spirit of St. Louis to be wheeled outside. The weather had been too bad the night before to move the plane to Roosevelt Field. Six Nassau County motorcycle patrolmen escorted the concealed plane, which was tied to the back of a truck, and was hauled across the deeply rutted road to Roosevelt Field, where Lindbergh had planned to make his departure.

At 2:30 a.m. on a misty Friday morning, May 20, 1927, Lindbergh rode from the Garden City Hotel, where he and the other contestants were staying, to Curtiss Field to prepare for take-off. Even at that early hour, 500 on-lookers waited. At 4:15 a.m. the rain stopped. Lindbergh ate one of the six sandwiches he had been given the night before and ordered the Spirit of St. Louis to be wheeled outside. The weather had been too bad the night before to move the plane to Roosevelt Field. Six Nassau County motorcycle patrolmen escorted the concealed plane, which was tied to the back of a truck, and was hauled across the deeply rutted road to Roosevelt Field, where Lindbergh had planned to make his departure.

Take-off for Paris

With the nose of the plane pointing toward Paris, Lindbergh worried about the take-off. He would have 5,000 feet to lift off the ground and gain enough altitude to clear the trees and telephone wires at the end of the field. The Spirit of St. Louis had never been tested carrying 425 gallons, let alone the 25 gallons of extra fuel Lindbergh ordered added (the capacity of the tanks as built came out oversize by 25 gallons). If it weren’t for the water-soaked runway, the lack of headwinds, the heavy humidity that would lower the engine’s r.p.m., and the untested weight of the plane, he would not have been as concerned. A bucket brigade formed to fill the plane’s five fuel tanks, and by 7:30 a.m. the tanks were filled to the brim. Hundreds more people joined the crowd. With the wheels sinking into the muddy ground, Lindbergh readied himself for take-off, mentally going over his checklist and gathering all his flying experience from the past four years. Should he wait or go ahead? There were too many uncertainties, except his trust and experience in this custom designed plane.

At 7:51 a.m. he buckled his safety belt, put cotton in his ears, strapped on his helmet, and pulled on his goggles and said, “What do you say — let’s try it.” At 7:52 a.m., Lindbergh took-off for Paris, carrying with him five sandwiches, water, and his charts and maps and a limited number of other items he deemed absolutely necessary. The heavy plane was first pushed, then rolling, and finally bounced along the muddy runway, splashing through puddles. At the halfway point on the runway, the plane had not yet reached flying speed. As the load shifted from the wheels to the wings, he felt the plane leave the ground briefly, but returned to the ground. Looking out the side window, Lindbergh could see the approaching telephone lines. Now less than 2,000 feet of runway remained and he managed to get the plane to jump off the ground, only to touch down again. Bouncing again, and with less than 1,000 feet, he lifted the plane sharply, clearing the telephone wires by 20 feet. At 7:54 a.m. he was airborne.

33 hours, 30 minutes, and 29.8 later at LeBourget Field, Paris

33 hours, 30 minutes, and 29.8 later at LeBourget Field, Paris

Although he had no forward vision during the flight (except a small periscope), and fighting off fog, icing, and overwhelming fatigue, he navigated his journey to a perfect landing 33 hours, 30 minutes, and 29.8 seconds later at LeBourget Field, Paris where a huge crowd of 150,000 on-lookers awaited his arrival. At that very moment when he was pulled out of his plane, the 25-year-old farm boy from Minnesota was transformed into the most famous hero the world had ever known.